I discovered parallel texts on my language-learning journey. On one page is your native language (L1); directly opposite is the target language (L2). Reading this way creates a side-by-side experience that supports comprehension as you move through the text. Although parallel texts have their critics, I enjoy them.

Here’s what the TeachVid blog says:

“Much of what is written in support of parallel texts is along the following lines:

They allow users to directly compare the L1 and the L2, which helps promote ‘noticing’.

The ability to compare the way vocab and structures are formed and combined in the L2 with reference to the L1 equivalent promotes this noticing of differences which may not happen if students only had access to the L2 text.

They allow users to access texts beyond their level.

Readers can read an L2 text and have constant recourse to an L1 equivalent so that they can check that they are understanding what they are reading.

Parallel texts can indeed be a powerful tool, if used by motivated language learners who really are using the time with the texts to understand how the L2 works, forming hypotheses and checking and confirming that they understand correctly what is happening with the language.” ~ In Support of Parallel Texts

Critics argue that parallel texts make it too easy to lean on the L1 page for understanding—and I get that. I see the same impulse in my French class at the International Language School. We all breathe a sigh of relief when we slip into English to work through the challenges of L2.

As researcher Andira Abdallah notes in her paper:

“Based on my experience as a second language instructor, it is very hard, if not impossible, to eliminate the first language use during the collaborative work of students in a second language learning environment especially when the majority of these students share the same L1.” ~ Impact of Using Parallel Text Strategy on Teaching Reading to Intermediate II Level Students

Josh, my French teacher, encourages us to read stories that are already familiar to us. While he doesn’t explicitly promote parallel texts, he strongly affirms the underlying principle: knowing the storyline reduces cognitive load, making it easier to engage with and absorb the target language.

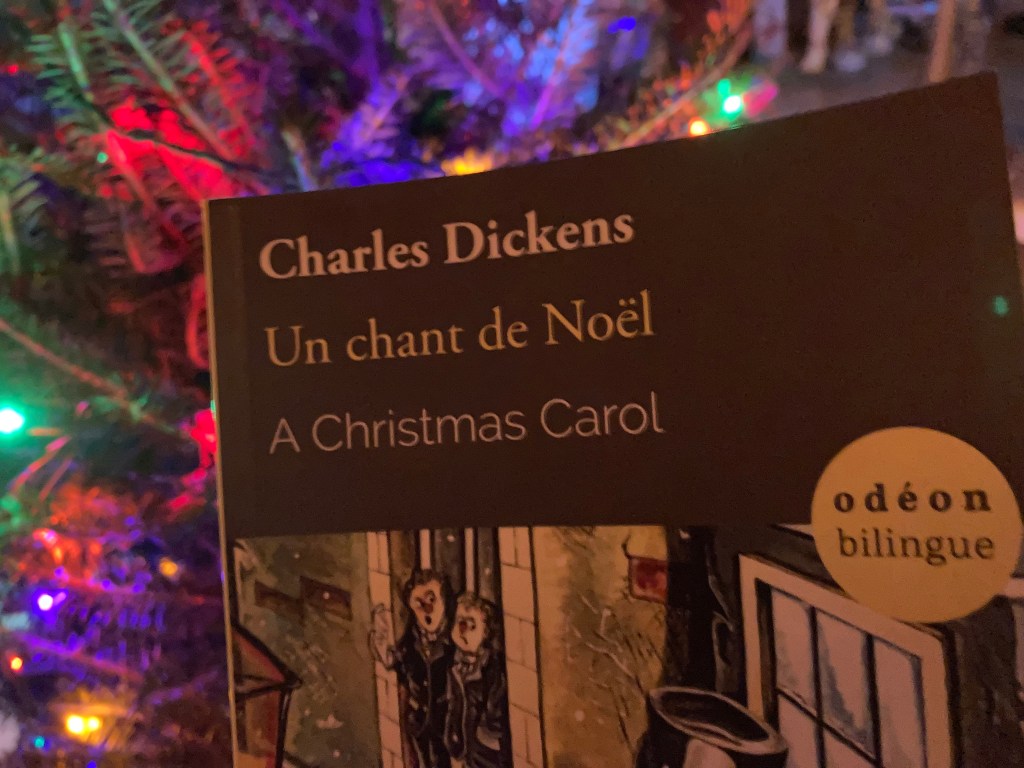

Here’s a bit from A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. Without access to your L1, can you understand what it says?

“Un chant de Noël, Chapitre 1

Le spectre poussa encore un cri, secoua sa chaîne et tordit ses mains fantastiques.

<< Vous êtes enchaîné ? dit Scrooge tremblant ; dites-moi pourquoi.

– Je porte la chaîne que j’ai forgée pendant ma vie, répondit le fantôme. C’est moi qui l’ai faite anneau par anneau, mètre par mètre ; c’est moi qui l’ai suspendue autour de mon corps, librement et ma propre volonté, comme je la porterai toujours de mon plein gré. Est-ce que le modèle vous en paraît étrange ? >>

Scrooge tremblait de plus en plus.

<< Ou bien voudriez-vous savoir, poursuivit le spectre, le poids et la longueur du câble énorme qui vous traînez vous-même ? Il était exactement aussi long et aussi pesant que cette chaîne que vous voyez, il y a aujourd’hui sept veilles de Noël. Vous y avez travaillé depuis. C’est une bonne chaîne à présent ! >>

Scrooge regarda autour de lui sur le plancher, s’attendant à se trouver lui-même entouré de quelque cinquante ou soixante brasses de câbles de fer; mais il ne vit rien.”

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol / Un chant de Noël: Bilingual Classic (English-French Side-by-Side). Odéon Press, [2017]. ISBN: 9781973451723